Glenn B. Pfeffer, MD, is director of the Foot and Ankle Center at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. He is also a co-director of the Hereditary Neuropathy Program and Co-Director of the Cedars-Sinai/USC Glorya Kaufman Dance Medicine Center. Dr. Pfeffer has written numerous scientific articles on orthopaedics and has edited seven academic textbooks on the foot and ankle. He has been treating foot and ankle problems in patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease for 25 years. He is a past president of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society and recently served as president of the California Orthopaedic Association. Dr. Pfeffer is frequently interviewed on foot and ankle topics and has been featured on CNN, Dancing with the Stars, Dateline NBC, Good Morning America, and in The New York Times.

Welcome to the second part of our series on the surgical correction of the high-arched (cavovarus) CMT foot, focusing on tendon transfers. In part 1, I wrote about the boney surgical correction of the heel (calcaneus). Take a look at your heel. Does it twist inward? You were not born with a turned-in heel. So how did it happen? The underlying problem has to do with an imbalance of the muscles in your leg.

Some nerves are more affected than others, which is what causes some of the muscles in your leg to be relatively strong, while others are weak. The strong muscles overpower the weaker ones, which causes the foot and toes to take the abnormal twisted position so common with CMT. As a patient with CMT grows during childhood and adolescence, the uneven pull of the muscles on the developing bones can cause them to become misshapen. Hence the need to surgically correct the heel bone (calcaneus), as discussed in part 1. Four main muscles contribute to the problem: the posterior tibial, tibialis anterior, peroneus longus and peroneus brevis. I think it is important to understand what they do normally, and what they do abnormally, with CMT. Videos on my Instagram account (@Charcotmarietoothsurgery) illustrate the difference.

First, some basic anatomy: Each muscle in the leg connects into the foot bones by a tendon, so when I talk about the pull of a tendon, I actually mean the pull of the muscle on the tendon. A tendon looks and feels like a big piece of al dente pasta. With every step, normal muscles function to balance the foot. In CMT patients, however, this balance does not exist. The imbalance that occurs between two important muscle groups causes most of the major problems. The first imbalance is between the tibialis anterior and the peroneus longus. The second is between the posterior tibial and the peroneus brevis.

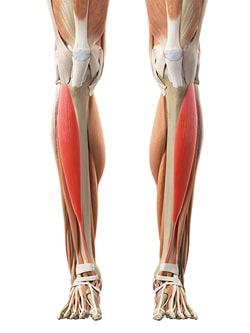

Figure 1:

The Tibialis Anterior

The tibialis anterior is the main muscle that lifts up the foot (figure #1). This muscle weakens early in the disease process. This is what causes foot drop, or at least diminished ability to dorsiflex at the ankle and lift the forefoot.

Figure 2:

The Peroneus Longus

Figure 3:

The Peroneus Brevis

The second major muscle imbalance has to do with the posterior tibial tendon and the peroneus brevis (figure #3). The posterior tibial tendon connects to the inside of the arch and helps support it, much like a cable on a suspension bridge. Its pull is normally balanced out by the pull of the peroneus brevis tendon, which inserts on the opposite side of the middle of the foot. These two tendons are what allow the foot to move side to side and stay flat on the ground when walking. In a CMT patient, the posterior tibial stays strong compared to the peroneus brevis and causes the progressive inward turn of the foot. That’s why many of you can turn your foot inward much better than you can turn it outward. The most important part of CMT cavovarus surgery is the balancing of these tendons, both to improve function and to minimize the use of braces.

If the posterior tibial tendon functions, it can be transferred from the leg to the top of the foot. This accomplishes two important things. First, it takes away the deforming force of the muscle that twists the foot inward. Second, it provides strength for the ankle to move up. This can make all the difference to someone who wants to avoid braces or who has feet that are not sitting flat within braces. At the same surgery, if the peroneus longus is also strong enough (which is usually the case), it is transferred to the outside of the foot into the peroneus brevis. This is done by sewing the tendons together. This transfer takes away the deforming force of the peroneus longus that is pulling down the inside of the foot and creates a stabilizing force to prevent the foot from twisting inward. CMT surgery is all about taking away the strong tendons that are deforming the foot and transferring them to strengthen the weaker tendons.

Figure 4:

Toe Extensor Tendons

A final key transfer has to do with the toe extensor tendons that run down the top of the foot (Figure #4). If sufficiently strong, I frequently transfer these tendons into the midfoot, at the top of the arch. The toes no longer deform upward from over-pull of the tendon, and foot drop is minimized. Although not commonly done in the United States, I find that this transfer is often the key to a successful surgery. I am very proud that Max Michalski, MD, my previous resident, and our CMT team at Cedars-Sinai recently won a national first place prize for our published research on this technique.

The longer the muscle imbalance is in place, the worse the deformity becomes and the harder it is to correct with surgery. Big problems start small. Even if your CMT progresses, it is important to balance the foot and minimize further deformity. Please see an orthopedic foot and ankle specialist early.